A Guide to Air Purity Standards for Compressors

The Critical Role of Air Purity in Dental Practices

Clean, dry, and contaminant-free compressed air is not a luxury in a dental clinic; it is a fundamental requirement for patient safety and equipment longevity. Every time you use a handpiece, air/water syringe, or other pneumatic tool, the compressed air comes into direct contact with patients and the internal mechanisms of your expensive equipment. Contaminated air—carrying water vapor, oil aerosols, or solid particulates—can compromise clinical outcomes, lead to infection, and cause premature failure of dental instruments.

From a practical standpoint, I have seen high-end handpieces fail in a fraction of their expected service life. The culprit wasn’t a manufacturing defect but persistent moisture carryover from an undersized or poorly maintained compressor dryer. This leads to internal corrosion and sluggish turbine performance, frustrating the practitioner and creating unexpected repair costs. Ensuring your air supply meets specific purity standards is a cornerstone of modern clinical operations and a key tenet of quality management frameworks like ISO 13485:2016, which governs medical device quality systems.

Decoding Compressed Air Quality Standards: ISO 8573-1

The primary international standard for compressed air quality is ISO 8573-1. It defines purity classes for three main types of contaminants: solid particles, water, and oil. The standard uses a three-digit code (e.g., [P, W, O]) where each number corresponds to a specific purity class for each contaminant, respectively. For dental applications, a stringent purity level is required to protect patients and ensure tools function correctly.

While regulations can vary, a common benchmark for non-surgical dental air is ISO 8573-1:2010 Class 1.2.1. Let’s break down what that means.

| Contaminant | ISO 8573-1 Class | Maximum Permissible Level | Why It Matters for Dentistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Particles | Class 1 | ≤ 20,000 particles at 0.1-0.5 µm ≤ 400 particles at 0.5-1.0 µm ≤ 10 particles at 1.0-5.0 µm |

Prevents clogging of fine nozzles in handpieces and air/water syringes. Reduces the risk of introducing foreign matter into a treatment site. |

| Water | Class 2 | Pressure Dew Point (PDP) ≤ -40°C (-40°F) | Prevents microbial growth within air lines and tanks. Stops corrosion and freezing within delicate instrument mechanics. Ensures bonding agents cure properly. |

| Total Oil | Class 1 | ≤ 0.01 mg/m³ | Prevents oil aerosols from contaminating restorative materials (compromising bond strength) and from being inhaled by patients. Protects sensitive o-rings and seals. |

Achieving these standards is not just a matter of purchasing an “oil-free” compressor. It requires a systemic approach to air treatment, which is a core requirement under medical device regulations like the EU MDR and the FDA’s Quality System Regulation.

Debunking a Common Myth: “Oil-Free Means Pure Air”

A frequent misconception is that an oil-free compressor guarantees pure air. While oil-free designs eliminate the risk of introducing lubricant oil into the airstream, they do nothing to remove other contaminants drawn in from the ambient environment. Atmospheric air is filled with water vapor, dust, pollen, and microorganisms. Without a proper filtration and drying system, the compression process concentrates these contaminants, creating a hazardous mixture that can be delivered straight to your point of use.

Building a Compliant Air System: A Step-by-Step Guide

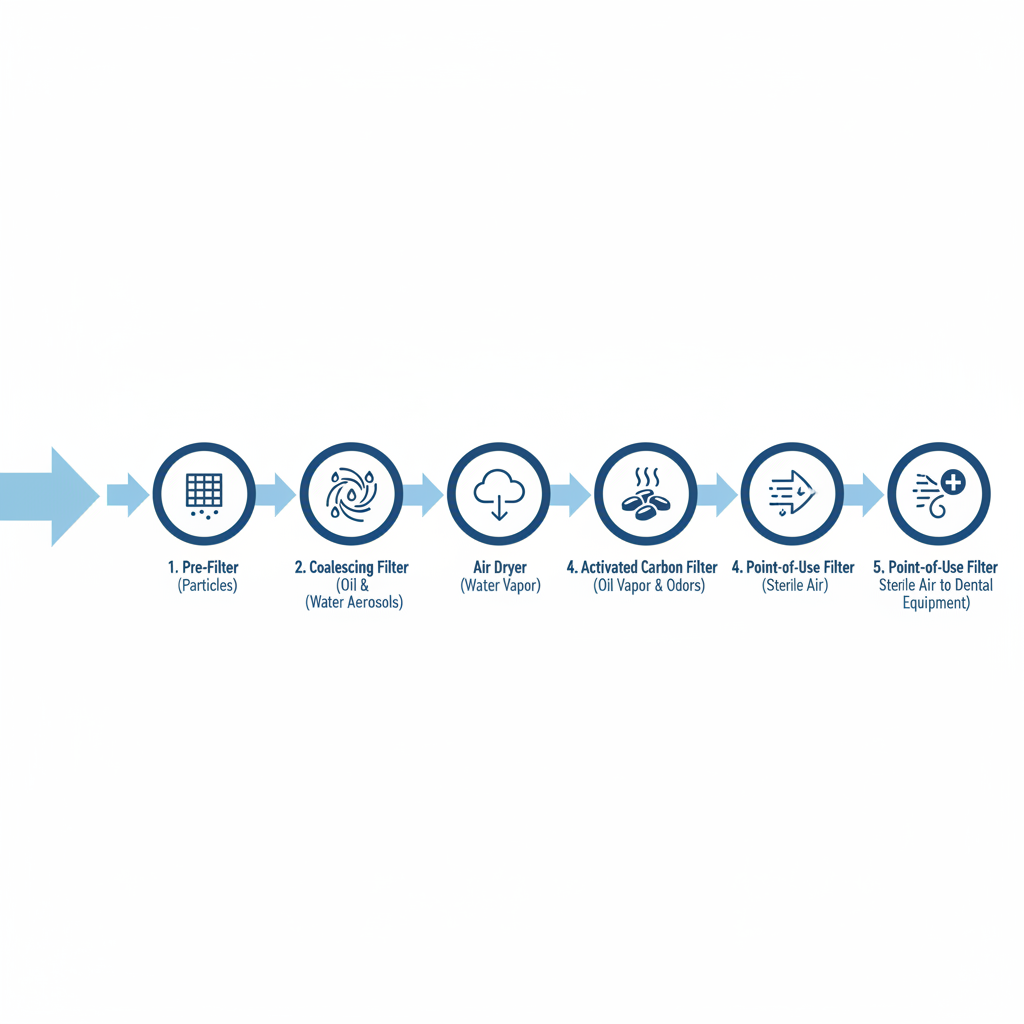

Achieving Class 1.2.1 air purity involves a multi-stage treatment process. Skipping a step or using undersized components is a frequent cause of failure. The correct sequence is crucial for each stage to work effectively.

- Pre-Filter: Placed just after the compressor tank, this filter removes bulk liquid water, dust, and larger particles (typically down to 5 microns). It protects the more sensitive filters downstream.

- Coalescing Filter: This is a critical step for removing fine oil and water aerosols. It forces tiny droplets to merge (coalesce) into larger ones that can be drained away. A high-efficiency coalescing filter can remove aerosols down to 0.01 microns.

- Air Dryer (Refrigerated or Desiccant): This is where most of the water vapor is removed to achieve the required pressure dew point (PDP). For most dental clinics in temperate climates, a refrigerated dryer that cools the air to around 3°C (37°F) is sufficient to prevent liquid water from forming in the lines. However, to strictly meet the -40°C PDP of Class 2 water purity, a desiccant dryer is necessary. Desiccant dryers use materials like silica gel to adsorb water vapor, achieving much lower dew points but typically requiring higher initial investment and maintenance.

- Activated Carbon Filter: This stage removes oil vapor and other hydrocarbon odors through adsorption, providing the final polish for oil-free air down to Class 1 levels.

- Point-of-Use Sterile Filter: As a final safeguard, a sterile filter (often 0.01 micron) should be installed at the point of use, such as at the junction box for the dental chair. This ensures any potential contamination from the air lines themselves is captured before reaching the patient or handpiece.

Designing this system correctly from the start is a key element in future-proofing your operatory for new technology, ensuring your core infrastructure can support increasingly sensitive equipment.

Common Pitfalls in Air System Management and How to Fix Them

Even with the right equipment, poor maintenance and testing protocols can undermine air purity. I’ve seen clinics invest in top-tier systems only to have them fail due to simple oversights. Here are the most common mistakes and how to address them.

Pitfall 1: Testing at the Wrong Location

The Mistake: Sampling air for testing only at the compressor outlet in the utility room.

Why It’s a Problem: The air quality at the compressor can be vastly different from the air delivered to the patient. The extensive network of pipes leading to the operatory can harbor moisture and biofilm, re-contaminating the air after it has been treated.

The Fix: Always perform air quality sampling at the point of use—the connection to the dental unit or handpiece. This is the only way to validate that the air reaching the patient meets clinical standards.

Pitfall 2: Ignoring Differential Pressure

The Mistake: Changing filters based on a fixed calendar schedule (e.g., every 6 months) instead of their actual condition.

Why It’s a Problem: Filter lifespan varies dramatically with humidity, usage, and ambient air quality. Waiting for a scheduled date can mean you’re using a clogged filter for months, which restricts airflow and can even collapse, releasing a burst of contaminants. Conversely, you might be replacing filters that are still effective, wasting money.

The Fix: Monitor the differential pressure (ΔP) gauge across your filters. This gauge measures the pressure drop between the filter’s inlet and outlet. A rising ΔP indicates the filter is becoming clogged. Most filter manufacturers specify a maximum ΔP (e.g., 6-10 PSID). Change the filter element when it reaches this limit, not when the calendar says so.

Pitfall 3: Neglecting Condensate Management

The Mistake: Relying on manual draining of tanks and filter bowls, or failing to check automatic drains.

Why It’s a Problem: A compressed air system strips a large amount of water out of the air, which collects in the receiver tank and filter housings. If not drained, this water gets re-entrained into the airstream, overwhelming the dryer and carrying moisture and microbial contaminants to your tools.

The Fix: Use automatic, zero-loss drains on your tank and filters. Check their function monthly by manually activating them to ensure they are discharging water and not stuck.

A Practical Schedule for Validation and Monitoring

To ensure ongoing compliance and safety, a documented testing and maintenance plan is essential. This creates a record of due diligence for regulatory audits and provides peace of mind.

Recommended Air Quality Testing Schedule:

- Baseline: Perform a full, lab-analyzed air quality test immediately after installation of a new compressor system to confirm it meets the target ISO 8573-1 class.

- First Year: Conduct quarterly testing to establish a performance trend and ensure the system remains stable under varying seasonal conditions (e.g., high summer humidity).

- Ongoing: Once the system has proven stable for a full year, you can typically move to biannual testing.

- Immediate Action: If any test exceeds the specified limits, the system should be shut down, inspected, and serviced immediately. Having a spare set of all filter elements on hand is a crucial best practice.

Key Takeaways

Ensuring your dental compressed air meets stringent purity standards is not just a regulatory hurdle—it is a critical component of patient care, risk management, and operational efficiency. Achieving compliance requires thinking beyond the compressor itself and implementing a complete system of filtration, drying, and monitoring.

By understanding the principles of ISO 8573-1, avoiding common maintenance pitfalls, and adhering to a consistent validation schedule, you can protect your patients, prolong the life of your equipment, and create a foundation of safety and trust in your practice.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the most important standard for dental air compressors?

For air purity, ISO 8573-1 is the key global standard. A common target for dental practices is Class 1.2.1, which specifies limits for solid particles, water (dew point), and oil.

How often should I have my dental air quality tested?

Test upon installation, quarterly for the first year to establish a baseline, and then biannually once the system proves stable. Always test at the point of use.

Is an oil-free compressor enough to meet purity standards?

No. An oil-free compressor eliminates the risk of adding lubricant to the air, but it does not remove the water vapor, microorganisms, and particulates drawn in from the surrounding environment. A multi-stage filtration and drying system is always required.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical or engineering advice. Dental clinics should consult with qualified equipment technicians and adhere to all local, state, and federal regulations regarding medical gas and air purity. Always refer to the manufacturer’s specifications for your equipment.